Last time we examined the very first rail lines built in Japan after the Meiji Restoration. For part 2 of our series in anticipation of John Dougill’s forthcoming Off the Beaten Tracks in Japan, we’re moving a bit further along in the history of Japan’s railways. Those of us familiar with America’s history of westward expansion will have some idea of the vast scope of the companies that sprang up in order to build and manage the railroads. Not only did these companies own vast swathes of land and fantastic wealth, their size meant they were often involved in industries far removed from rail transport. This speaks to a general pattern of development, in no way exclusive to America, where railways are among paramount drivers of economic development. For this series, I was interested in what this looked like in the Japanese context. However, I was spurred to ask this question from an unlikely source: the Takarazuka Revue. How did Japan’s all-female theater troupe lead me back to railways in the early twentieth century? If you, like me, we’re unfamiliar with the Revue and its establishment, you might be surprised by the answer.

The expansion of Japanese rail in the late nineteenth century brought about the formation of several large railway companies. However, Japan departed from the American pattern in 1906 with the Railway Nationalization Act, which brought most of the major railway companies under control of the Ministry of Railways. This wasn’t the end of privately held railways in Japan in toto; main lines were nationalized while local lines and light rail continued as private entities. This is the context in which the Hankyu Railway Corporation was formed.

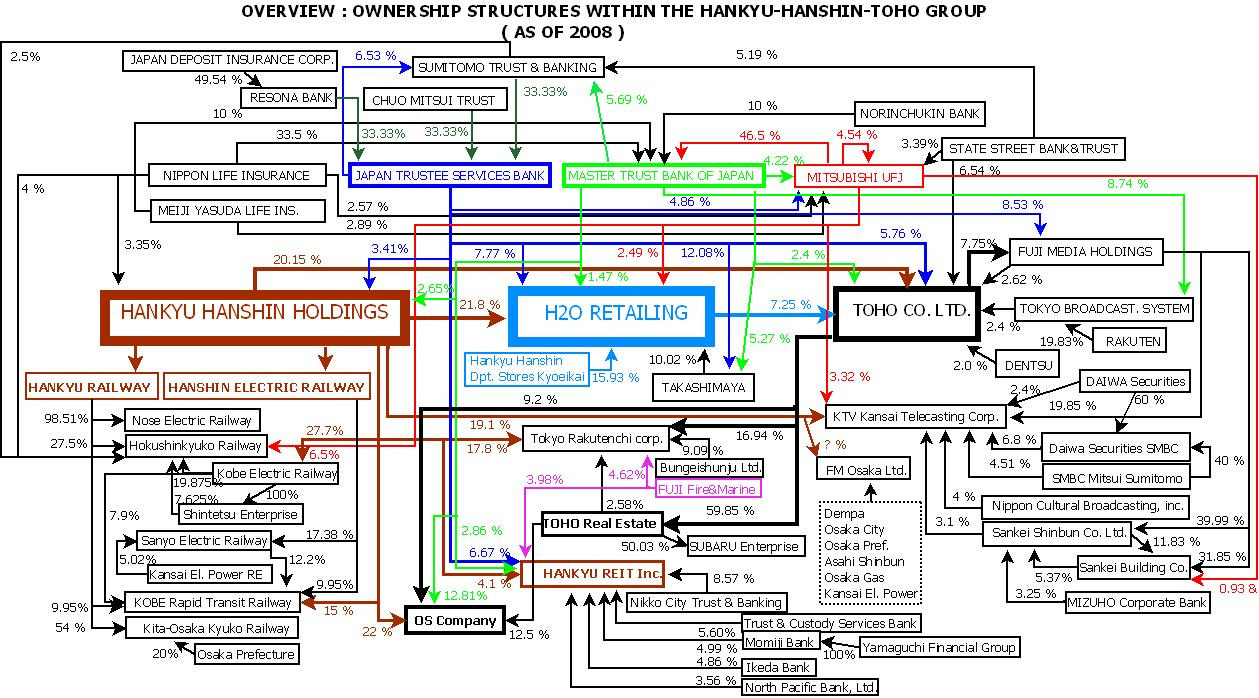

In 1907, Ichizo Kobayashi became director of the newly founded Mino Arima Electric Tramway Company—later to become Hankyu Railway—servicing the Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe metropolitan area. Kobayashi was a consummate industrialist of the Meiji and Taisho periods and served in the government during the period of Japanese empire. Fast forward to today, the Hankyu Hashin holding company is a sprawling entity—itself enmeshed within a complex of financial interests—that still bears the mark of its forefather. Under its purview we find media companies, such as Toho and Fuji Media; real estate, Hankyu Hanshin Properties; retail, H20 Retailing; and of course railways. Unsurprisingly, the Hanshin Tigers are today under the Hankyu Hanshin corporate umbrella, but the Orix Buffaloes (previously the Hankyu Braves) were yet another child of Kobayashi’s. It’s hard to overstate Kobayashi’s extensive and eclectic influence.

While this all certainly speaks to the complex structures of modern capitalist ownership in Japan and elsewhere, but it also bears a trace of its origins. Beginning at the turn of the twentieth century, Kobayashi’s concern was promoting a particular strategy of transport-centered urban development. Half a century on from Japan’s emergence from feudal rule, the question became how to appeal to the tastes of an emergent bourgeoisie with retail, housing, and entertainment.

In 1910, a rail connection from Osaka’s Umeda Station to Takarazuka, a city between Osaka and Kobe, at the time nothing more than a small hot spring village, was established. Osaka was prospering hugely from Japan’s industrialization and came to rival the Tokyo of its day in population size. Kobayashi’s dilemma as director of the Mino Arima Company was how to make the peripheral Takarazuka line profitable, and he played on the desires of those who wished (and had the means) to escape the city as it became more crowded and polluted. His efforts began with Paradise, an onsen and indoor pool struggling to attract customers. The pivotal decision was to infill the pool in favor of a stage and a theater troupe inspired by a Western-style ensemble employed by the Mitsukoshi Department Store. Thus the Revue was born.

What began as a supplement to the spa soon outstripped the popularity of the other amenities. By 1924, the Revue, now the main draw, moved into the Takarazuka Grand Theater; by the 1930s it had become a national phenomenon with an additional theater in Tokyo. The history of the Takarazuka Revue is fascinating in itself and as an index to the successive periods of modern Japanese history, from its participation in Japanese wartime nationalism to the beru bara boom of the 1970s. The gender politics of the Revue are a fascinating and unavoidable topic, but it suffices here to point out how it departs from classical Japanese theater. The traditions of kabuki and noh theater have, despite its origins in the case of kabuki, been an exclusively male pursuit since the seventeenth century. The Revue departed this custom. But one should not jump to the conclusion that this was a wholly liberatory development. The women of the Revue were as a rule to be unmarried, emblems of “modesty, fairness, and grace” according to the Revue itself. Change was certainly afoot, a transition from the outmoded morality of the early modern period to a newly adopted bourgeois domestic morality just as a feudal agrarian economy was transitioning into an industrial capitalist one.

Sources:

A Century of Dreams and Romance: A History of Japan’s All-Female Takarazuka Revue. Nippon.com. June 4, 2014. Access.

Beru Bara Tag Boom: The Takarazuka Revue. I say, you say, Heisei. April 16, 2012. Access.

Kobayashi Ichizō: The Visionary Impresario of the Takarazuka Revue. Nippon.com. June 9, 2014. Access.

Sakai, Yuna. The Takarazuka Revue and the Depiction of Gender Stereotypes Since 1914. Digital Humanities and Japanese History. Access.

I’ll leave off here without commenting more on the specific style of the Revue or their performance history, an interesting topic in it's own right. For a more in-depth account, I highly recommend the cited blog post from Beru Bara Tag Boom, which introduced me to the topic.

And stay tuned for October’s installment. You can preorder and learn more about the forthcoming title Off the Beaten Tracks in Japan on our website.