This is the third and final installment of our series on the history of Japanese rail. What struck me about John Dougill’s Off the Beaten Tracks in Japan was how each destination had its respective history, connected through the physical journey by train. I sought to invert this formula, connecting the history of rail to Japan as a whole. I had no intention off relaying a total history, rather to narrate a selection of historical vignettes. For the final piece, I thought it necessary to move outside the confines of the Japanese islands and onto the Asia continent where at the turn of the twentieth century Japan was engaged in imperial competition with the European powers of the day. Railways were central to the conflicts that unfolded, as I hope to illustrate below.

The period between the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War saw an immense expansion of rail in Japan. What interests us here is how this expansion surpassed the limits of Japan proper. As Japan’s influence extended into the region more broadly it was borne, of course, by ship but also by train. Japan’s imperial ambitions within its regional sphere would find it at odds and entangled with the competing interests of European powers, imperial Russia in particular.

To begin to paint a picture of the prevailing conditions during First Sino-Japanese War it’s helpful to mention another well known railway: the Trans-Siberian Railway. The Russian Empire began construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway in the 1890s as part of its effort to expand influence in China and Korea as well as connect western Russia to its eastern ports. The division of China by European powers had been an ongoing since the mid-nineteenth century; Japan was a latecomer to the parceling up of the ailing Qing Dynasty, and its proximity to Russia made it a natural rival. Japan, feeling it had something to prove, would be the first to take action.

Korea’s history closely ties it to both China and Japan, and its position between the two would make it the ideal pretext for Japan’s foray into China. The war was decidedly one sided in favor of the Japanese, further evidence that Meiji Japan had come into its own as a modern power while Qing China crumbled under antiquated institutions. To wit, China had hardly any railways built at the onset of the conflict, making troop movement across the vast Chinese territory painfully slow. The postwar period would mark a turning point in the development of rail across China. Like in Japan, rail would be built by foreign experts with Chinese labor albeit on foreign concessions.

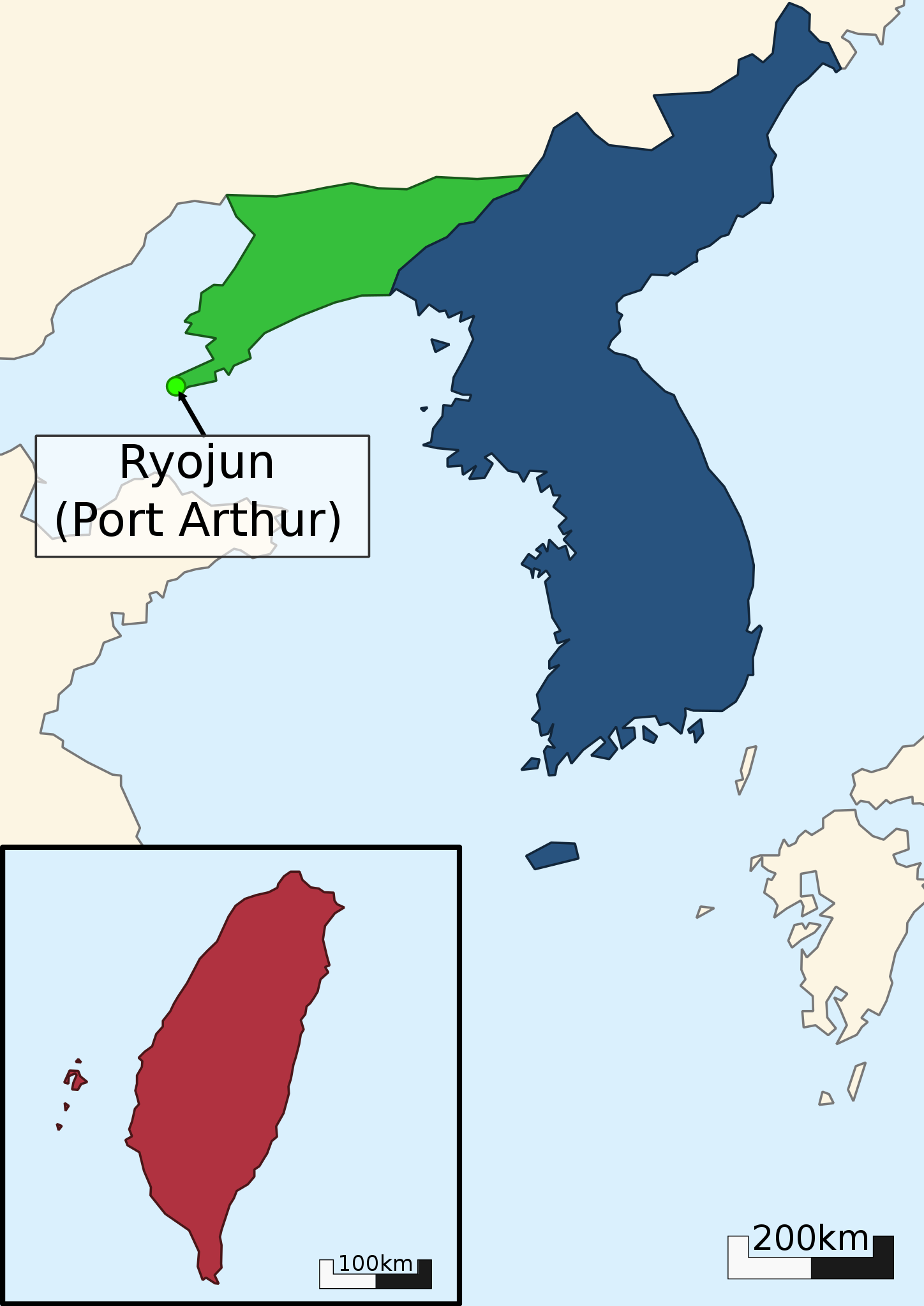

Along with the annexation of Taiwan and de facto influence over the Korean Peninsula, Japan had exacted the Liaodong Peninsula and its critical port cities in the Treaty of Shimonoseki. This last concession would be short lived as a diplomatic conspiracy of European powers helmed by Russia interceded to block the upstart Japanese. In a clear display of realpolitik, Japan was prevented from securing its claim to Liaodong and in turn Russia gained influence over the Liaodong territory, its ports, and much of northeastern China. It’s hard to exaggerate the centrality of rail to the Russian strategy. In 1897 it would begin building out the Chinese Eastern Railway, a network of rail that effectively connected the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok by way of Harbin as well as to the port of Lüshun (commonly known as Port Arthur). Manchuria had effectively become a Russian concession.

Japan assessed the Russian posture as both a threat to its ability to expand its own influence and an encroaching threat to Japan itself. It resolved to take the Russian fleet at Lüshun by surprise; the opening salvos of the Russo-Japanese War occurred in February of 1904. Japan’s relatively robust rail system enabled the swift and covert movement of troops to southern naval bases. By contrast the winter assault had not only left the Russia Pacific Fleet at Vladivostok frozen at port, it hampered the movement of Russian troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway. Harsh Siberian winters aside, the trans-Siberian route was left incomplete at Lake Baikal and required a ferry to cross the significant body of water. At first glance what appears to be a primarily naval conflict hinged on railways.

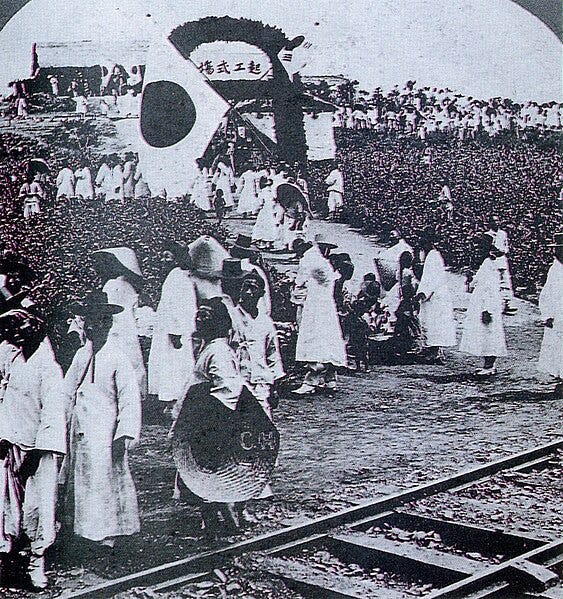

For Japan’s part, it too had been building rail on the continent. In 1989 Japan was granted a concession by the Korean government to build a rail line from Busan to Seoul. Like much of the rail in Japan itself at this time, this was undertaken by private contractors, though very much in the national interest. When the conflict between Russia and Japan began, the newly inaugurated Tetsudo Rentai (“Railway Regiment,” a sort of rail engineering corp created on the German model) was brought in to oversee the swift completion of the project. By January 1 of 1905, the Busan–Seoul line was in service. With a brief ferry trip across the Korea Strait, the journey from Tokyo to Seoul was now a journey by train.

The Japanese advance up the Korean Peninsula was unabated and soon crossed the Yalu River, the natural border between Korean and China. It was not long after, as Japan moved into Liaodong, that the southern portion of the Chinese Eastern Railway connecting Dalian and Port Arthur to Harbin was cut off by Japanese forces. The Tetsudo Rentai went about converting the Russian-built track to Japanese rail gauge standards so that Japanese locomotives and freight cars could be brought over. Once Russia’s position at Port Arthur and Dalian were neutralized, Japan was, ironically, able to make use of the railway to supply its own war effort while Russia was primarily dependent on the Trans-Siberian line.

After the war, the southern line of the Chinese Eastern Railway under Japanese control would be renamed the South Manchuria Railway, presaging the perhaps more familiar history of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria roughly two decades later. One way to read this period of history is by reading the rails—in their extent and their changing of hands—as an index of imperial ambition.

References:

Free, Dan. Early Japanese Railways 1853–1914: Engineering Triumphs That Transformed Meiji-era Japan. Tuttle Publishing, 2008.

Nakano, Akira. Korea's Railway Network the Key to Imperial Japan's Control. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 5 (9). September 3, 2007. Accessed here.

That’s it for Episodes in the History of Japan’s Railways. Off the Beaten Tracks in Japan will be available on November 7. You can preorder and learn more about the book on our website.